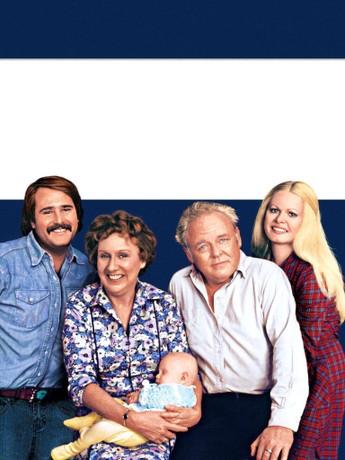

Growing up in 1970s Texas, prejudice wasn’t a shocking event; it was the wallpaper. Racist slurs, sexist jokes, and casual bigotry were part of the everyday soundtrack of my community, so common they rarely registered as wrong. My world was a clear, unquestioned division between “us” and “them.” I accepted this as the immutable order of things, a reality too entrenched to challenge. Then, into our living room came “All in the Family,” and with it, the character of Michael “Meathead” Stivic, portrayed by Rob Reiner. Watching him wasn’t just entertainment; it was my first real lesson in moral courage.

The show presented a battle I’d never witnessed: a young man using reason and empathy to confront the entrenched ignorance of his father-in-law, Archie Bunker. Archie’s bluster and bigotry mirrored the attitudes I heard all around me. But Meathead’s responses—calm, persistent, rooted in a belief in basic human dignity—showed me a different path. For the first time, I saw someone not just disagreeing with prejudice, but systematically dismantling it with compassion as his primary tool. It wasn’t about winning an argument; it was about defending a principle. This televised clash of worldviews created a quiet earthquake in my own mind, forcing me to question the “normal” I had always known.

Meathead’s character was more than a liberal mouthpiece. He argued for fairness with a palpable sense of empathy. His goal wasn’t political victory in the abstract, but the tangible respect of every human being. In my insulated Texas environment, this was a radical concept. The show didn’t preach; it dramatized the personal cost and necessity of these difficult conversations. It made the moral choice feel tangible and, crucially, possible. I realized that challenging the status quo wasn’t an act of rebellion, but an act of humanity—something I could, and perhaps should, attempt myself.

The long-term impact was a slow, steady awakening. “All in the Family” planted a seed that grew as I did. It reframed justice not as a distant political concept, but as a daily practice of empathy. It taught me that ignorance, like Archie’s, could be challenged, not accepted as a fixed trait. Decades later, I still see echoes of those living room debates in our national discourse. The legacy of Meathead, for me, is the enduring understanding that the most powerful stance isn’t always the loudest, but the one firmly grounded in kindness and an unwavering belief in everyone’s right to dignity. That quiet lesson from a 1970s sitcom became the compass for my own worldview.